- Return to Article Of The Month index

Controlling Mole Crickets on Bahiagrass Pasture with Nematodes

June 2000

Dr. Martin B. Adjei - Range Cattle Research & Education Center

Non-indigenous mole crickets are the major insect pest problem on bahiagrass pasture in Florida. Approximately 75% of the 3.5 million acres of improved pastures that support the 1.2 million head cow-calf industry in Florida consist of bahiagrass pastures. Since 1996, about 400,000 acres of bahiagrass pasture have been destroyed by mole cricket infestation, in addition to an annual hay revenue loss of $6 million to livestock producers. Consequently, Florida cattlemen are seeking a cost-effective and permanent solution to the damage.

Mole Crickets

Two species of pest mole crickets are prevalent in south Florida pastures. These are the southern and the Tawny. A third one, the short-winged, is restricted to coastal areas. Adult mole crickets are about an inch long, light brown in color, and have front legs that are well adapted for tunneling through the soil. All were introduced around 1900 at the seaports of Brunswick, Georgia in the ballast material of ships from the Atlantic Coast of South America. From the port, the southern and Tawny mole crickets spread westward and southwards. They have become serious pests in Florida because they have few natural enemies, Florida's sandy soils favor their development and multiplication, and above all there are millions of acres of their favorite host grasses - bahiagrass and bermudagrass.

Southern Tawny Short-winged

Mole crickets damage pastures in two major ways:

- By tunneling through the soil near the surface, they loosen the soil, uproot and dry out grass root systems.

- They feed on grass roots, causing dieback and eventually bare soil.

The Tawny mole cricket is the most serious pest on bahiagrass pasture because it eats all parts of the plant (leaves, stems and roots). Southern mole crickets feed mostly on soil insects and other small animals. Most mole cricket feeding takes place in the night after rain showers and during warm weather. During the night they feed on above-ground parts, biting off stems and leaves, which are dragged into the burrows to be eaten. Roots may be eaten at anytime. Both nymphs and adults come to the surface at night to search for food leaving tunnels in their path and they return to their permanent burrows during the day where they may remain for long periods of time during cold or dry weather. When mole crickets come to the soil surface in daytime (say during flooding rains or mating flights) they are subjected to predators including fire ants, ground beetles, raccoons, skunks, armadillos and several birds.

Tawny Mole Cricket (Scapteriscus. vicinus)

Adult mole crickets are strongly attracted to specific sounds and to lights during their spring dispersal flights. Mole crickets deposit their eggs in chambers dug out within the upper 6 inches of soil. A female will excavate three to five egg chambers and deposit about 35 eggs in each chamber on the average. In south Florida, egg laying usually begins in early March, reaches a peak in May but may continue throughout the year. Approximately 75% of total eggs are laid by the month of June. Eggs deposited between May and June require about 20 days to hatch but longer time is required during cooler periods. Peak egg hatching occurs from June to August in south Florida.

Monitoring

Mole cricket numbers at any site are estimated by three main methods:

- Soil Flushing

- Pitfall Trap

- Sound Trap

For the flushing method, mix 3 fluid ounces of dishwashing detergent in 5-gallon pail-full of water, and drench 4 square feet with this solution. Observe the area for about 2 minutes and count the crickets as they surface.

Linear pitfall traps are ideal for monitoring live young (nymphs and juveniles) mole crickets on a pasture. They are constructed by cutting a slot approximately 1 inch wide length-wise in a section of 3-inch diameter PVC pipe. This pipe is then buried in the ground so the slot is at or slightly below the soil surface, with one end feeding into a 5-gallon bucket and the other end capped. Four 10-ft PVC pipes as described feed into a bucket to form the trap.

Pitfall Trap

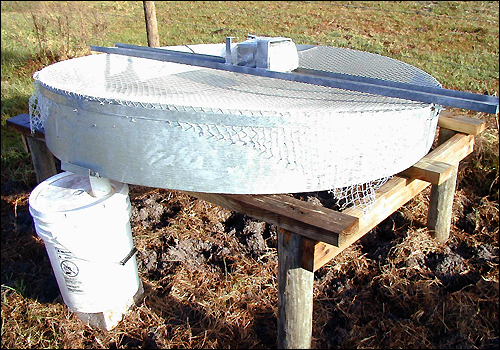

Sound traps attract adults to the highly amplified synthetic or recorded call of male mole crickets. A Sound Trap consists of a caller situated over a collecting device that catches the crickets as they land. The collecting device may be as simple as a child's wading pool filled with water or a specially constructed aluminum frame (with a 1.5m diameter) covered by a fishing net which feeds into a collecting bucket. Sound traps are effective only during flight seasons in spring and fall and only adults are taken.

Sound Trap

The record nightly catch for a "standard" sound trap used by the University of Florida is 17,000 Tawny mole crickets on March 21, 2000.

Mole Cricket Nematodes

Nematodes that infect and kill insects also known as entomopathogenic nematodes have been known since the 17th century but it was only in the early 1990's that Dr. Grover Smart Jr. of the University of Florida selected a specific type called the "mole cricket nematode" (Steinernema scapterisci). This nematode was imported into Florida from South America, the original home of pest (scapteriscus) mole crickets.

Mole cricket infested with mole cricket nematodes (Steinernema scapterisci).

An area in the anterior part of the intestine of the infective juvenile nematodes is modified as a bacterial chamber. In this chamber, the infective juvenile nematode carries cells of a symbiotic bacteria which are usually of the genus Xenorhabdus. The nematodes act as vectors, transporting their bacteria symbionts into the blood stream of an infected mole cricket host, inducing a lethal septicemia usually within 3 days of infection. The bacteria contribute to the symbiotic relationship by providing nutritional requirements for their nematode partners during reproduction in the insect cadavers. The bacteria also maintain suitable conditions for nematode reproduction in dead mole crickets by producing antimicrobial substances that inhibit the growth of a wide range of other micro-organisms.

Inside the mole cricket, the juvenile nematode feeds on bacteria and their metabolic products, and molts to males and females which mate and produce two generations of juveniles. The late second-stage juveniles cease feeding, incorporate a pellet of bacteria in their bacterial chamber, and molt into the third stage (infective) juveniles which leave the cadaver in search of new host. The cycle from entry of infective juveniles nematodes into a mole cricket host to emergence of new infective juveniles usually takes 7 to 10 days and as many as 50 thousand infective nematodes may emerge from a dead mole cricket. Hence, insect control with nematodes may be self-sustaining under appropriate environmental conditions.

Commercial Production of Mole Cricket Nematodes

The University of Florida acquired a patent (#5,165,930) on the use of mole cricket nematode as a biological control agent in 1993. Methods for large-scale, efficient and reliable rearing of the nematode (based on techniques of solid culture and liquid fermentation) were developed and nematode efficacy of mole cricket control was demonstrated in Florida for a period of three years (1993-96). Unfortunately, however, the nematodes reproduce and spread slowly on their own in the field and they have not been commercially available since 1996. The reason being, the only U.S. company with capacity for mass production discontinued its operation. A new mole cricket task force consisting of a consortium of IFAS researchers, extension personnel, and affected clientele groups, especially the Florida Cattlemen Association, was initiated in June 1999 to:

- Re-establish a commercial source of S. scapterisci.

- Initiate a state project to produce and distribute the nematode.

- Test reduced quantities in various field application arrays.

- Conduct practical research to improve rearing, storage, shipping and application methods.

- Keep all interested partners informed and involved.

Based on preliminary market information collected, the office of Technology and Licensing of the University of Florida agreed to base royalties for the licensed use of this nematode on sales, rather than require advanced payments. Some of the leading nematode producers around the world are showing interest in this new deal.

Another option pursued by the task force involves funding from the state. A biological agent, such as nematode for mole cricket control, is often produced and distributed by a government agency because the magnitude of its market and associated profitability may be limited. In pursuit of this option, a budget was submitted to the FDACS which received favorable response subject, of course, to the standard legislative appropriation procedures. Under this plan, UF-IFAS will provide technical support to train, certify and monitor applicators. Nematodes will be produced and distributed at no cost by the FDACS but applicators would be paid for their services. We continue to keep our fingers crossed for this plan to be funded.

Meanwhile, under the UF-IFAS Florida FIRST Initiative, a research grant of $15,000 was awarded to the research committee for the purchase of nematodes from Australia for field trials and for the design of application equipment. With permits from both FDACS/DPI and USDA/APHIS, the nematodes were imported (at a cost of $410 per acre at an application rate of 800 million nematodes per acre). The nematodes have been applied to a bahiagrass pasture in central Florida with a high concentration of mole crickets. Application was done in strips to cover 0, ⅛, ¼, and ½ of the one-acre pasture plots each in three replicates.

The equipment designed and tested allowed for subsurface injection with 100 gallons of water per acre to protect nematodes from ultraviolet light and excessive heat.

The spread of infected mole crickets from the different arrays of field distribution will be monitored for several years to determine the rate of spread of nematodes across pasture. In summary, the new mole cricket task force has formed partnerships within the research, technology and clientele community, secured a legislative supplemental budget request for the FDACS, submitted a Florida FIRST Initiative Project proposal (funded) and obtained nematodes for field tests in central Florida. These efforts require continuous communication (as done here), coordination and diligence to sustain momentum on controlling pasture mole crickets.